Fukazawa Yutaka: Metafiction and Multimedia in Eroge

Author: beef2929

First published 2023/08/31

1. First Novel (2010)

Before we dive into the main subject of today’s post, we need to talk about an unusual little project called First Novel. Released physically and digitally in 2010, First Novel is a collection of five short stories on the shared theme of neurological disorders, each written and illustrated by a different pair of creators. The talent here caught my attention—First Novel is a veritable reunion tour of some of the most recognisable eroge scenario writers of the early 00s, including a couple of my favourites. I’d like to kick off today's post by going through these stories one-by-one.

『音の色』by Karabe Yousuke, a.k.a. Setoguchi Ren’ya (CARNIVAL, SWAN SONG, KIRA☆KIRA), who might just be my all-time favourite author. Taking inspiration from Russian literature, Setoguchi has penned feverish, stress-inducing nightmares with nauseating precision and consistency for going on two decades now, and this story serves as a microscopic showcase of how harrowing his stories can get. The protagonist and heroine both suffer from auditory-visual synesthesia, which means they both 'see' sounds in their heads. They bond over their shared experiences until prejudice and a misdiagnosis thrusts them into harm’s way. It’s nice to see Setoguchi operate in an unfamiliar form—a standalone short story is something of a rarity for him, with his only other one still trapped in an exorbitantly expensive unscanned doujinshi from 2005.

『二十一番の喪失』written by Ichikawa Tamaki (Flyable Heart and later the Leyline trilogy) and sporadically illustrated by her long-time collaborator Itou Noizi (Flyable Heart and literally Haruhi Suzumiya). I was totally unfamiliar with these two and with Union Shift in general, but I was impressed by what I read here. The protagonist’s synesthesia (he sees numbers as shapes) helps him illustrate a deck of tarot cards for a girl in his art class. There’s not a whole lot to say about this one; the story is simple and the writing is easy to process while still coming off as elegant and emotional. Good stuff.

『終わらない階段』by Tanaka Romeo (CROSS†CHANNEL, Rewrite, Jintai)--my other favourite author, as the links in those parentheses will vouch. Romeo has a lot of short stories under his belt; he's renowned not only for his eroge but also for his light novels, among which this story feels right at home. We follow a teenage girl with a condition I can only describe as a kind of ‘physical empathy’—whenever she observes any physical contact around her she feels it as if it was happening to her own body—as she struggles through her daily life at a school that has recently been overrun by soulless machines of destruction that roam the halls. I’m not actually sure whether or not Hasumi’s condition is based on a real neurological disorder, but it makes for a unique and engrossing point of view–in true Romeo fashion, it comes to feel relatable in spite of or even thanks to its abnormality. His text here is as pithy and incisive as ever and the interplay between the two central metaphors kept me invested from start to finish. He manages to cover a lot of ground here and bring it all home with one killer final line of dialogue: 人をまっすぐ見るのって、楽しいね

『夏影』by Uminekozawa Melon, who is an eroge creator in the same sense that THE STALIN are movie stars–he made one eroge, twenty years ago, that nobody seems to have played, though inexplicably its tie-in novel (Hidarimakishiki Last Resort) became a cornerstone of early 00s otaku media. Uminekozawa has since authored light novels and mainstream SF alike, published essays, self-help, interviews with scientists, lyrics for denpa idol groups, a BL-themed reimagining of Kojiki; he’s been a construction worker, a host, a yakuza member, a radio host, a board game creator and he’s currently the guitarist in an all-author rock band. This guy deserves his own deep dive. Natsukage, named after the AIR song, is a spoopy horror story about a girl with synesthesia (specifically, she associates tastes with ultra-specific memories and concepts) getting revenge on some kids who bullied her for her condition. It’s the most generic story of this collection and I found it pretty forgettable, but learning about Uminekozawa has brought immeasurable joy to my life and was worth the price of admission alone.

『たまねぎ現象には理由がある』by Motonaga Masaki with art from established mangaka kashmir. Motonaga is well-known for producing a bunch of hit titles (Sense Off, Mirai ni Kiss wo, Princess Bride) in the early 00s for 13cm/130cm/otherwise… a.k.a. AyPio, the brand behind SEX 2. You can bet your ass I'll be cashing in on that tenuous link if I ever become a Motonaga megafan–and I just might, because this was great! It's less of a short story and more of a short novel, inexplicably dwarfing every other story in this collection; in fact, it's as long as all of them combined. This leaves the 思考回路 feeling a little winding and long-winded, but the substance is compelling with a powerful central metaphor and genuinely unpredictable twists and turns. Our protagonist suffers from hemispatial neglect, a condition that leaves him unable to direct attention towards stimuli on the left side of his field of vision/hearing/etc. The titular ‘onion effect’ is that the harder he tries to concentrate on his right side, the further and further his field of perception shrinks–now he can only register the right side of the right side of his vision, and so on. His actual senses are unaffected by all of this, his brain simply can’t process the information it’s receiving. Kenta is by far the most disabled of all the characters featured in this collection. His narration never shies away from the alienation and cynicism this brings to his life, which casts his relationships in a pretty interesting light. This story veers so wildly off-course that it ends on a note doubling as an indictment of our ability to understand one another and a farcical parody of twists in storytelling, and somehow… Motonaga kinda pulls it off? This is not the most refined story of the bunch but I’ll be damned if it isn’t the most memorable and ambitious.

All in all, this is an awesome and diverse collection of stories, but I'm still intrigued by the author selection here. For reasons we'll touch on shortly, Motonaga and Uminekozawa's landmark works of early otaku metafiction make them natural candidates, but the others? To me this feels, more than anything, like an eroge nerd using his position to commission new stories from a bunch of his favourite authors. A noble cause if there ever was one, of course. But who exactly is this patron of the arts?

2. Doujin Days (1996-1999)

Fukazawa Yutaka has been a die-hard eroge fan since the early 90s. He first appeared on the scene himself in September of 1996 with the launch of his fansite FLAGYX N()TE. The site has been offline since 2002, but Fukazawa went to the effort to preserve some of its content by publicly archiving his ancient blog posts. On FLAGYX N()TE, Fukazawa would post news and impressions about the latest releases from Leaf (Shizuku, Kizuato, Saorin, ToHeart), elf (Be-yond and YU-NO) and Tactics/Key (MOON., Kanon, AIR), curate lists of his and his readers’ recommendations, and even run individual BBS boards and popularity polls for his favourite games. The site hosted fanfiction submitted by community members alongside amateur games Fukazawa made in his free time. These included a bunch of now-lost shooting and puzzle games (DF, Grass X and its impeccably titled sequel Grass X to SKY) and Hitomi, an impressive fangame for Shizuku and Kizuato that simulates the look and dimensions of the original PC-98 games in html, and which Fukazawa would later port to the actual PC-98. But it’s Fukazawa’s original creative fiction, not his community or fanfiction, that secured him a spot in the history books.

I’m gonna take a quick detour to provide a general overview of Fukazawa’s work here. While you might expect an eroge otaku as ardent as he was to produce something transparently derivative, Fukazawa is a surprisingly idiosyncratic and unique creator. I tend to think of him as being a programmer and game designer first and a writer second, because he takes a very ‘mechanical’ (for lack of a better word) approach to storytelling and communicates his ideas directly through plot devices and interactivity just as much as through his words themselves. I know it’s a cliche, but the medium really is the message when it comes to Fukazawa. He's known for his extensive use of metafiction; in fact, I can't think of anybody whose reputation and body of work revolves around metafiction to the extent that Fukazawa's does. When you think of metafiction in eroge, your mind probably goes straight to fourth-wall-breaking genre commentary—seminal games like Shuusaku, Totono and『ドキドキ文芸部!』—but Fukazawa seems uninterested in that. You won’t find any insightful commentary here about video game characters having feelings, you won’t feel ashamed of any words or deeds or be forced to [X] INTROSPECT, Fukazawa just has an innocent love for layering stories-within-stories and representing ideas with other ideas.

So if his stories aren’t about eroge, what are they about? I’d say the most consistent throughline is grief. Fukazawa likes to depict the fallout of personal tragedies, our attempts to fill the holes left in our hearts by the loss of our loved ones. He looks at how these events can traumatise us and trigger psychological disorders, conditions he portrays with an unusual authenticity that tracks with his approach to storytelling–he treats their causes and symptomology much the same way he treats plot mechanics in his stories, as connected minutiae that construct a big picture. The metafiction lends itself quite nicely to both of these themes. The constructed realities can serve as insights into maladaptive minds while the process of representation replicates how we try to ‘replace’ lost loved ones with something (or somebody) new as we scour for a path forward. There are other recurring elements, like love triangles and age-gap (especially teacher-student) relationships, but these are the basic building blocks of a Fukazawa story.

1997: 『忘れものと落とし物』

To celebrate the six-month anniversary of FLAGYX N()TE’s launch, Fukazawa serialised a story titled Wasuremono to Otoshimono throughout April of 1997. This story is for all intents and purposes Fukazawa’s true debut as a creator, and it's a fascinating debut at that. Wasuremono is an early example of Japanese hypertext fiction—Fukazawa described it as a “web-based adventure game”. It took the form of a fake blog being run by a middle-schooler, with hyperlinks in each entry leading to first-person accounts of the events as they transpired as well as more enigmatic scenes alluding to sinister secrets. To blur the lines between fiction and reality, this fake blog was identical in design to the actual FLAGYX N()TE blog and updated in real time over the course of the month.

Wasuremono allows an unassuming budding romance between a nameless boy and a nameless girl to morph into a surreal, existential panic attack, all the while leaving a breadcrumb trail of clues and foreshadowing that are painstakingly explained one by one at the game's conclusion. Despite its clumsy execution, this makes for an immensely satisfying payoff where every minute detail ends up being relevant in some way to the twist, and I can only imagine how impressive it must have been to Fukazawa's friends and fans in 1997. Wasuremono is heavily inspired by Jungian archetypes and the then-contemporary anime series Evangelion, particularly the relationship between Shinji and Misato. In that regard, the game ultimately takes a direction that even I have to admit I found a little tasteless given its subject matter. I have to stress that while I praised Fukazawa’s authentic portrayals of psychological conditions earlier, the same cannot be said for their treatment. Eroge, of course, requires a suspension of disbelief. In real life, our mental problems are rarely sucked and fucked away. But it’s a suspension of disbelief that is especially difficult to grant Fukazawa when he’s so invested in the real features of these disorders and goes as far as to name-drop them. If you’re the kind of person who was annoyed by Sayooshi not featuring realistic CBT, I suspect you’ll find yourself irritated by Fukazawa’s stories. But I feel a little guilty for dwelling on this–at the end of the day, Wasuremono is a sincerely impressive passion project made by a young, aspiring creator.

In 2005, Fukazawa remade Wasuremono from the ground up as an actual freeware adventure game, downloadable through FLAGYX’s successor LANGuex. This version is more accessible and boasts a thoroughly revised script and some nice ambient music cues, but it also robs the game of its original context and format. No longer are you exploring chains of hyperlinks, you’re just reading a sequence of detached standalone scenes. Moreover, the game feels sluggish, owing to its very frequent use of an effect where a line appears character-by-character in slow-motion, programmed so that even if you have instant text display on, the screen will just freeze for however long it would have taken before the line finally appears. Between the daunting, unpolished browser game and the refined but annoying-to-play standalone game, I have to say I personally prefer the former. Thankfully both are contained in the download from LANGuex.

1998: 『LU/RARARA.LU』

Following Wasuremono, Fukazawa set his sights back on traditional downloadable games and began working on his very own visual novel engine, iterations of which would be named FLAGYX, nbook and LANGuex over the years. The engine's defining characteristic was its 'memo system': instead of a backlog, readers could copy and paste text directly from the script into a persistent field tied to their save file. This system essentially closes the distance between the reader and the text; I think this is Fukazawa backporting some of the user-friendliness from his html-based imitations eroge into the real thing. This engine was used to build Fukazawa's first original novel game, the enigmatically titled anthology story LU/RARARA.LU. It featured cameos from Wasuremono and I… think the title is another Jung reference…? Just twenty copies of an unfinished version of this game, featuring one of the several planned perspectives, were circulated at Comiket 54, while an even less finished version was made available to download. Fukazawa declined to redistribute either of these when rebuilding his website in 2002, owing to tentative plans to revive the project someday that have never come to fruition. To my knowledge, neither have seen the light of day since, and LU/RARARA.LU remains a simultaneous case of vaporware and lost media.

1999: 『チュートリアルゲーム』

In 1999, Fukazawa started creating and distributing free games to test the nbook engine. The first three of these, collectively DEBAG GAME, were extremely short, barely more than a few minutes each with gimmicks like “what if there was a cult that used computer words like overflow error”. There’s not much to say about these. Tutorial Game, from May of 1999, has loftier goals. In it, you’re a tech-savvy teenager teaching his hot teacher how to use the nbook engine. One might naively assume Tutorial Game will teach you how to make your own game in the nbook engine, but it’s actually meant to teach you how to play an nbook game. This is obviously hilariously self-explanatory and unnecessary but this premise ends up being a jumping-off point for a story that immediately gets out of hand.

Tutorial Game being inspired by elf’s Hiruta Masato was a statement that brought me no shortage of confusion until it dawned on me that it’s an obvious pastiche of 1995’s Isaku, particularly in its portrayal of the depraved villain Aoki. The game is supported by a lot of inventive and dynamic presentation tricks. MIDI tracks are layered so ‘instruments’ can be faded in and out seamlessly over a continuous beat; coloured textboxes dance across the screen, overlapping to show us when scenes occur simultaneously, kinetically cannibalizing each other during the brawl at the climax of the story. It’s just a joy to play and it never stops being funny that this is all in a game called fucking Tutorial Game. The final act is genuinely tense and exciting, but I must admit I have no idea how to guess the ‘solution’ and had to dig through the internal files to proceed (sorry). I also have no idea what this mysterious URL you unlock as a reward for completing the game was supposed to lead to... But all this digging did bring my attention to an index file where Fukazawa outlines his future plans, which apparently consisted of making pornographic Tutorial Game DLC for his private collection. He's my hero.

It’s hard to know for sure–maybe it was the gimmick all along, but I’m in love with the image of Fukazawa setting out to write a simple engine tutorial and getting so attached to the setting and characters that he accidentally turns it into an Isaku-inspired thriller, complete with backstories, drama, romance and like seven named characters. I think it speaks to the wild, inventive energy Fukazawa had at this point. The man was firing on all cylinders, and nowhere can you see this clearer than in the unproduced Truelove knot. Fukazawa had been getting serious about his work and started applying to undisclosed commercial eroge brands throughout 1999. The way you did this, at least back then, was by writing and submitting design documents called 企画書. 企画書 are meant to give a general overview of a game and its selling points–the basic premise, structure, heroines, CGs, etc. Fukazawa’s Truelove knot 企画書, which he would publish on his website years later, was a 60,000+ character monstrosity with flowcharts, detailed summaries of every single scene… at one point it even contained a fully playable html-based demo. 60,000 characters of Japanese, for those unfamiliar, is the length of a short light novel. They must have thought he was insane.

Truelove knot did not get Fukazawa hired, but FLAGYX N()TE did. A member of his community put him in touch with a brand named Force (a homonym of "4th", for whatever reason) who were in their infancy and looking for scenario writers. Impressed by the games on his site, they hired Fukazawa and let him make the games that would define their brand.

3. Fukazawa at Force (2000)

Everything I’ve discussed so far has been extensively documented by Fukazawa himself, but few people share his interest in archiving history. Force released their first game in August of 1999 and their last just 11 months later before vanishing without a trace. It’s difficult not only to ascertain anything about their inner workings, but even to attain the products they put on the shelves. Fukazawa himself has no clue who owns the rights to their IPs and the games have never been reprinted in the two decades since their releases, so the only legal option is to buy them second-hand. The only problem? The emergence of an unexpected cult following around the games themselves pushing demand so far beyond supply that the games have achieved infamy as the rarest, most expensive items on the market. The cheapest copy of Shoin, I could find online right now was going for 250,000 yen—a steal compared to the 500,000+ yen it goes for elsewhere.

In their one year of existence, Force released no less than four commercial eroge, three of which were written by Fukazawa and two of which he created and programmed by himself in nbook. I can't even imagine how tight the deadlines Fukazawa must have been given to make these games were, and it's hard to ignore in the final products. Despite being commercial eroge, sold in big glossy cardboard boxes and everything, these games are janky, way jankier than his solo projects. They're low-budget, unvoiced and full of typos, inscrutable grammar, scripting issues, characters calling each other the wrong names, dialogue having incorrect nametags, dialogue and narration getting mashed up into the same textbox… If you can think of a mistake, it’s probably in one of these games.

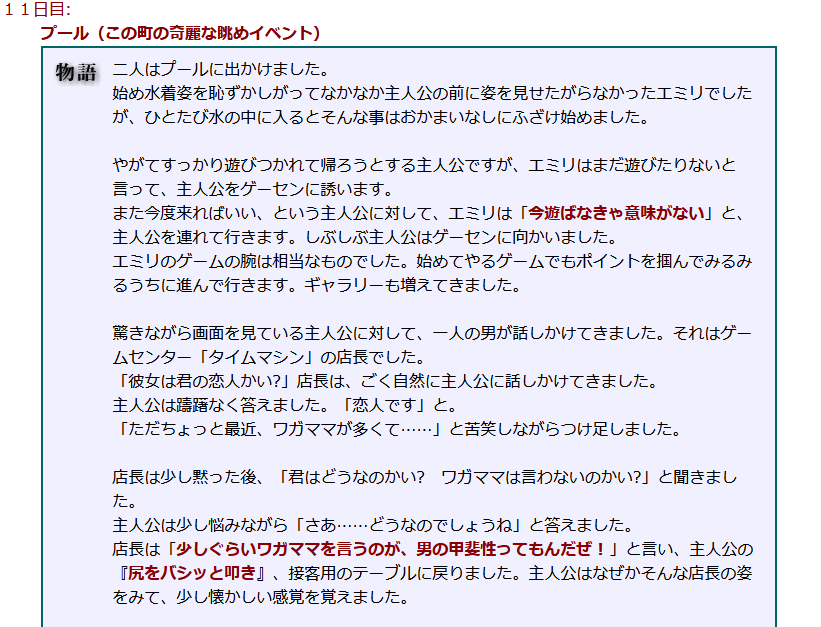

Fukazawa's first job with Force was writing Izayoi, a 調教 ("training") nukige set in a secluded house in the middle of a steep mountain based loosely on the gameplay loop of the aforementioned Truelove knot. It's the only Fukazawa game that doesn't really feel like a "Fukazawa game", and this post is long enough as it is, so let's instead direct our attention to 2nd LOVE, released in February of 2000. 2nd LOVE is the game from Fukazawa's catalogue most transparently, single-mindedly about grief. Just months after a traffic accident claims the life of our protagonist Kiyoshi's girlfriend, she reappears before him, now just 25cm in stature [TL note for Americans: very little] and invisible to everyone but him. The heroines (including, of course, Kiyoshi's teacher) are themselves coping with the loss of their respective loved ones. This shared trauma becomes both the foundation of and an obstacle to their relationships with Kiyoshi, as both parties struggle with what it means to move on from somebody so dear to you and 'replace' them with somebody new. As these relationships find solid ground, Kiyoshi's mini-gf disappears, and the story… resets.

This is Fukazawa's biggest innovation here, these relationships take place not in branching heroine routes but in linear sequence. Some 90s games like Shuusaku would loop until you found your way to the true ending, but I think 2nd LOVE might have been the first to actually integrate this mechanic canonically into the story itself, with Kiyoshi retaining his memories from each loop. While the time loop structure would become an inescapable staple of eroge, it has a very specific purpose in 2nd LOVE: it's yet another way in which the game implements its central theme of moving on from someone and finding new love—it's what the title refers to, after all. So I don't get the impression Fukazawa realised he was doing anything groundbreaking here. He just went with the structure that best suited the story he wanted to tell, and accidentally predicted the next decade of eroge in the process.

The game certainly doesn't outstay its welcome; its twist ending, contained in a final scenario deliberately titled 3TH LOVE, is so abrupt that it almost feels anticlimactic despite turning the entire story on its head. The more I reflected on it, though, the more I came to appreciate how it inverts and compliments the game's content at the same time. It's really clever, even if the execution leaves a little to be desired. Also, because I couldn't forgive myself if I moved on without mentioning it—2nd LOVE's soundtrack owns. Once again it's 100% MIDI music, but the tracks are still stuck in my head weeks after I played it. Somebody needs to rip these ASAP.

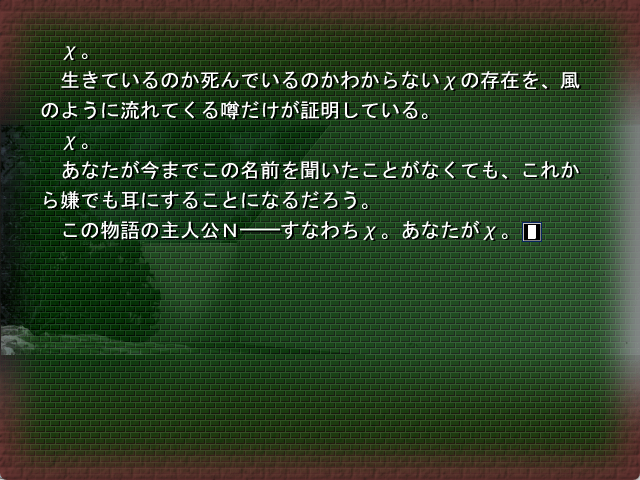

Even after getting delayed, Force's final game released just five months later. 2nd LOVE may have been ahead of its time, but 『書淫、或いは失われた夢の物語。』(henceforth Shoin,) adopts a structure so novel that it hasn't really been replicated since. For any English-only readers, I should note that「、或いは」 is used in essentially the same way that ", or" was in English titles of classical literature. But Shoin,'s title isn't offering us two descriptions of the same story—the game actually contains two separate stories built out of the same assets, accessible from the main menu and available to explore at your own leisure. These stories, each full of branching paths and endings, are engineered so that if you hit a dead end in one, exploring the other will help you progress. In one, you are the everyman eroge protagonist on a peaceful vacation with your gf-to-be; in the other, you are a career rapist on a secret rape mission from Rapist MI6. In both, you find yourself and three female guests trapped inside the mansion resort with no way to contact the outside world.

These competing stories, their interactions and contradictions, carry the game all the way across the finish line. It's one of the best hooks in any eroge I've played, you're immediately compelled to figure out what the fuck is going on here and the game makes good on this trust, stringing you along until its final moments. There are, of course, other tricks in its playbook too, other ways the game keeps your attention. Its use of interactivity, for instance, extends beyond just giving you the freedom to explore the two stories. One quirk of the nbook engine I haven't mentioned yet is that choices are made via a text input prompt; generally this amounts to typing the number corresponding to the on-screen choice you want to pick, but theoretically you always have the option to type your own choice into that field instead. Shoin, is the first and only game to ever make extensive use of this functionality, with puzzles requiring the player to manually type out the solution.

The final stretch of the game, 4RD LOVE (yes, seriously), is more sophisticated in how it plays its hand than anything Fukazawa had yet written. No longer are you being sat down and explained the twist, you're piecing it together yourself from documents and POV switches and repressed memories! The twist itself is infinitely more deranged; even if you manage to figure out what's going on, the circumstances that led to it will catch you off-guard. And yet, somehow, it works, landing with a clarity and catharsis its predecessors lacked. At its outset, Shoin, seems a lot more cryptic and abstract than 2nd LOVE, but it ends up being much simpler, and all the more effective and memorable for it. There is also some deep significance to the fact that the fourth and final eroge by Force/4th ends with a section called 4RD LOVE. I have no clue what this significance could be, but there must be.

I can't tell you exactly when Force closed their doors, but I can tell you that Fukazawa was an ex-employee by the time Shoin, was released (he actually ran support for the game himself, though FLAGYX N()TE). This didn't mean he was out of ideas, though. Fukazawa immediately began conceptualising his next novel game, something called True Color, (and yes, the comma is important). If Force wasn’t going to make it, Fukazawa would simply make it himself. He officially announced the game alongside a playable demo and website in 2001 and even advertised it in a magazine in 2004, but despite his many attempts, LANGuex would never release True Color,.

In the decades since, Fukazawa has drifted further and further away from eroge, but he's been keeping busy. He’s pumped out doujin projects: a typing game, a puzzle game, the Wasuremono remake, some kind of email-based ARG… He’s also made a name for himself in the IT business, starting his own company named MONOGATA in 2014 and publishing iOS apps. He made a PlayStation® Home™ exclusive match-three arcade game. Most recently, and I swear this is true, he's joined a theatre troupe and become a stage actor. He’s in a play this November! Searching his name returns dozens of photos of a wonderful, idyllic リア充 life; here he is celebrating his birthday, which happens to be a couple of weeks ago (happy belated birthday, king). What endears me most about this all is that he isn’t the least bit ashamed of his eroge career, talking openly about it in interviews as recently as 2021. In a subculture where even the biggest creators tend to hide behind pseudonyms, I think that's wonderful.

But we aren’t done yet, because somewhere, amidst all of that, Fukazawa actually did manage to finish True Color,. Not by himself, but with the help of NIPPON FUCKING ICHI. As of the 29th of July, 2010, Fukazawa Yutaka was no longer the obscure indie dev responsible for two of the rarest games in an already niche medium—he was the creator of a PSP game published by the company who make Disgaea. Allow me to introduce the game formerly known as True Color,:

4. Second Novel (2010)

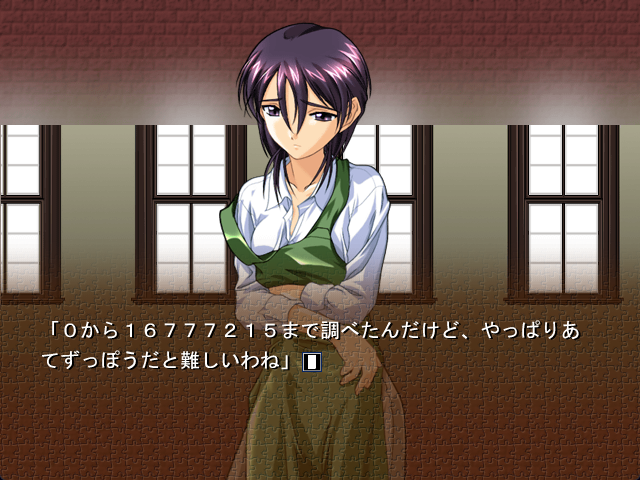

Throughout high school, Ayano, Yuuichi and Naoya were inseparable, until a tragedy puts Ayano in the hospital and Yuuichi in the grave. Five years later, Naoya returns to his tainted hometown and reunites with Ayano, who has not only repressed her memories of the event and its circumstances but lives with long-term, possibly permanent, anterograde amnesia–the inability to form new memories. Ayano is 22, but to her not a day has passed since she was still in high school, and she will need to relearn this disparity every fifteen minutes for the rest of her life. Ayano begins recalling a "story" about her life before Yuuichi's accident, from which Naoya appears to have been scrubbed. But she can only get through a few scenes at a time before her concentration and memory fail her. By finding branching paths and summarizing the narrative on flash cards, Naoya helps Ayano explore the once-forgotten "story" in search of the truth.

Fukazawa milks this fairly unassuming premise for everything it's worth and then some, transforming a few lingering doubts that barely even constitute a mystery into a web of shame, grief and lovelorn metafiction so tangled and convoluted that my first instinct upon completing the game was to google "second novel ending explained". It stands uncontested as his most ambitious and far-reaching story, reincorporating and building on just about every idea he's toyed with during his career (not only is its title a throwback to 2nd LOVE, the game references and even directly namedrops Wasuremono, Shoin, and True Color,). Attention to detail is the name of the game here, from the intricate plotting to the presentation. The production values are (obviously) the best a Fukazawa project has ever seen; all characters, including Naoya, are fully voice-acted, the event CGs are expressively and meaningfully composed and the opening and ending themes are moody shoegaze bangers I can't stop listening to. There is plenty to love about Second Novel, and after all this buildup I wish I could sit here and tell you Second Novel is one of my new favourite games. But I can't.

Much like Shoin, interactivity is inextricable from the structure and storytelling of Second Novel. You ricochet back and forth between reading "story" scenes and creating summaries of them, which involves reminding Ayano of story details by showing her a flash card from your growing collection (you end up with 195). At first, this amounts to pausing the story every few minutes to answer basic trivia questions like "what is the name of this main character again?" But the game soon gives up on even that much challenge and starts including narration like "Right, I should show her the <school rooftop> card…" before just about every selection. Second Novel settles for what I like to call "Dora the Explorer gameplay", where a game consists of telling you exactly what button to press and waiting for you to press it–an even worse example of this is the 2016 game √Letter. The experience won't even be salvaged by using a walkthrough, since the game is already its own walkthrough. This is the very worst kind of gameplay you can put in a game; it's patronising, mind-numbing busywork that feels designed to waste your time. Do we relate to or learn anything new about Ayano and Naoya through doing this busywork? Personally, I'm not convinced we do. Even if we were to generously assume that Second Novel is intentionally annoying to simulate the frustration of living with anterograde amnesia, it feels half-hearted–surely the challenge of having to actually work out the answers would make for a more authentic experience.

This problem is compounded in three main ways; firstly, by the narrative structure itself, which is extraordinarily repetitive to say the least. Ayano's "story" is broken up into "sections", and rather than forming a continuous narrative, these "sections" are closer to "retakes" of the story with the 怪談 of the Week swapped out for something new and a different combination of characters falling or almost falling from the school roof. This is a feature of the game I actually respect a lot—it adopts the structure of an unfinished story being rewritten over and over again in real time, with the same disturbing outcome showing up time and time again like an intrusive thought. But the main effect achieved by this structure is a deliberate lack of forward momentum or progress, inducing a sense of floundering. Alongside the already patience-trying gameplay, this is a hard pill to swallow. The pain is compounded secondly by the constant use of unskippable pauses between lines hardcoded into the scripting, which renders the game as sluggish as the Wasuremono remake. Maybe I am inordinately bothered by this, but I have never, in my life, played a game and thought "this is great, but I would love to not be able to read the next line for 5 seconds right now. Especially if that happened a dozen times in every single scene." I know how nitpicky this sounds on paper, but the material is just too basic and repetitive on its surface level to get away with forcing you to stop and bask in its ambience at every turn. And thirdly… look, we'll get to thirdly. For now let's give some more credit where it's due.

Pushing past the tedious first half of Second Novel will reveal a pretty complex narrative that goes beyond just rehashing Fukazawa’s greatest hits and covers a lot of new ground. I spoke earlier about how questionable the resolutions of Fukazawa's stories and the psychological recoveries of his characters tend to be, but Second Novel bucks the trend with an unexpected dose of reality (of course, his teacher fetish is back with a vengeance to compensate). The game is clearly interested not only in how anterograde amnesia works but also how a condition like it might impact one’s life and relationships. On top of this, the game's final section (which incidentally is called… no, not 5ST LOVE, but Section EX 2, or, as the flash card puts it: S.EX 2. I can't escape it!!!) pulls a trick best described as a total inversion of what the archetypal meta eroge aspires to, coming full circle by anonymising its characters rather than trying to imbue them with some approximation of sentience. In doing so, Fukazawa opts to leave certain questions unanswered and certain connections undrawn, a move that will delight some readers and frustrate others. It makes it difficult to take any clear message from the game, which has a lot on its mind at the best of times. The game's most central theme is how we construct and especially interpret narratives, but it also uses stories as a metaphor for our lives themselves. One plot point gestures towards the misprescription of SSRIs, another addresses family abuse.

To understand the appeal of Second Novel, we also have to consider its accessibility. It's always nice to see eroge staff get a chance to demonstrate their talent in a mainstream, all-ages format. This happens most often when an eroge writer writes a popular light novel, but that's obviously less feasible for someone whose skills lie in game design and interactivity. The barrier to entry for Fukazawa's games far exceeds them being R18 PC games too—keep in mind that just getting your hands on one will run you upwards of ¥100,000, and the stigma against piracy (even of obscure, out-of-print works) is enormous in Japan. Second Novel was the first opportunity a lot of eroge fans got to check out that Shoin, guy they'd heard so much about. It helps that even without comparing it to Shoin, Second Novel was a steal at just over ¥5,000 yen (¥4,000 digitally!), especially considering that price got you a full-length game and book in the same package. Speaking of which...

Remember First Novel, the short story compilation I went over, like, thirty paragraphs ago? It isn't just some tie-in, it's an actual part of Second Novel. While physical 文庫本 of the whole collection were printed and included as a preorder bonus, the stories are all accessible from the extras menu of the game itself, a new one unlocking every time you complete a "section" of the story. Imagine for a second that instead of frontloading all those short story impressions I just put one between every paragraph of this review. That would be pretty annoying to read, right? As much as I loved the stories, this is unfortunately the third compounding problem with Second Novel: you are constantly being distracted from the narrative by unrelated stories with more compelling content from more engrossing authors. Picture coming back from one of these tight, self-contained side stories, enduring the Dora the Explorer gameplay leading you through the same story beats as last time to pick up on a few new clues sprinkled in before being alerted that you've unlocked a new side story, and you finally understand what it's like to play the first half of Second Novel. If you play Second Novel, I encourage you to read First Novel all at once either before or after the main game. While we're on the topic, I'd also like to bring up Motonaga's story again. Certain elements of it have me questioning whether it's a deliberate homage to Fukazawa's work (the inciting incident, for instance, is the same vehicular bike accident that kicks off 2nd LOVE and Tutorial Game) and whether the layered twists at the end are Motonaga's 'take' on Fukazawa's approach to mysteries and reality in fiction. This is just speculation and I can't prove Motonaga is secretly a Fukazawa fan, but I did find this tweet alluding to him buying a PSP just to read Second Novel, which is pretty adorable however you slice it.

Despite all its polish, Second Novel is a very unusual, experimental game with a lot on its plate. It's overflowing with ideas that don't all work well together, but make for an entertaining, if frustrating, experience. And if nothing else, its central mystery was complex and intricate enough to keep me coming back for more. There was, however, a certain other mystery, no less puzzling than the game's, on my mind as I played and hopefully on yours as you've read: what is this? How did this happen? Why was a guy with two obscure eroge from ten years ago to his name poached by Nippon Ichi? Well, I guess you'll just have to think about it and come to your own conclusion…. your very own Second Second Novel…

I'm just kidding of course, I'll be kinder than Fukazawa and spell it out for you. Sometime around 2008, Fukazawa joined a collective named Text., a subsidiary of a company called Wizard Soft (oh my god, that’s why he made that PlayStation Home game). It was formed by Arakawa Takumi (Lien, Konoha Challenge), whose lifelong friend was working at Wizard Soft. Arakawa has been working in eroge since the 1990s, and so have the partners he reached out to, Fukazawa and Ootsuki Suzuki (Shuumatsu no Sugoshikata, Sabae no Ou). It wasn't just these three either—the staff of Second Novel is full of experienced eroge personnel, from its female seiyuu to composer Takumaru (Saihate no Ima), to vocalist Katakiri Rekka (Sharin no Kuni, Damekoi). I think Text. can be seen as a predecessor to ANIPLEX.EXE, a 'patron of the arts'-style label devoted to funding accessible projects from iconic eroge staff. On that note, it turns out Fukazawa wasn't responsible for the selection of authors featured in First Novel after all! He wouldn’t have dreamed of landing such an all-star lineup. In an interview with Getchu, he even recalls his delight upon learning who had been brought on, as if he was a fan again. No, these picks came from Arakawa, whose industry connections are not to be underestimated. Naturally, Arakawa was also the one who got Fukazawa in the door with Nippon Ichi, where he managed to sell them on the game that would soon become Second Novel.

Unfortunately, Text. was a short-lived project, disappearing after releasing just two titles, Second Novel (2010) and a game called Dead End (2011). The former was of course written and directed by Fukazawa, while the latter was written and directed by Ootsuki and was a revival of his Sabae no Ou 'gamebook'/CYOA-style eroge series; Arakawa never got to do one despite being the original founder. Text. had plans as recently as 2015, but these never materialised. Considering how much of a selling point accessibility was for Second Novel, it's worth mentioning that both of these games are not only untranslated but stuck on the PSP, a console that has been dead for the better part of a decade. Earlier this year, Arakawa's friend at Wizard Soft passed away; in July, he tweeted that he'd like to get Second Novel and Dead End ported to modern platforms to honour his friend and the games they made together. I really hope this happens; Second Novel definitely deserves more recognition than it got and Dead End... sounds like nothing I've ever heard of. We'll never get proper rereleases of 2nd LOVE or Shoin, but we might yet get remakes and maybe even translations of these games.

In the past I’ve stuck to reviewing my favourite games, so it might seem strange for me to write so much about a game I had mixed feelings towards. It's not just the sunk cost fallacy; I find Fukazawa's work endearing and his career trajectory fascinating and inspiring. Fukazawa is as much a pioneer as his idols were, even if he's too obscure to have had a quantifiable influence on other creators. When the tools to make an eroge weren't widely available, he made his own; when the rules of the medium didn't suit the stories he wanted to tell, he broke them. He pushed the boundaries with everything he made and was so inventive that his games are still novel to play decades later. I thought it was a shame that so little had been written about him in English and wanted to put some more eyes on him. Second Novel is a cool game with a broad appeal, and just because I couldn't pick out a main idea driving it doesn't mean one doesn't exist—I'm sure somebody else could probably write a post this long about its portrayal of narratives.

To finish us off, let's assign the game a score on SKULLFUCKERS® dot Wordpress™ dot Com's official Good GPS, Bad GPS© scale. Second Novel is like having a perfectly good GPS that no longer works because you left it out in the rain, so you hire somebody to follow you around and hand-draw a map for you, but every time you retrace your steps the roads have been meticulously rebuilt in a slightly different layout, so now you can't find McDonalds and your map guy is on the verge of a mental breakdown.

See you next time!